Five Facts and Five Myths About How Toddlers Eat

As adults, we need a pretty consistent amount of food each day, and the majority of us* tend to eat all or most of the food we fix ourselves (or get served or buy) at each meal and snack. This predictable pattern of eating is our ‘normal’, so it’s no surprise that it may inform what we expect of our little ones. But what many parents don’t know is that young children eat in a very different way from adults.

Forewarned is forearmed, right? Understanding toddler eating norms can really help you navigate what can be a tricky parenting patch. To help you know what to expect when it comes to your young child and food, we’ve outlined a few of the hallmarks of typical toddler eating, and we’ve busted a few myths too.

❓MYTH 1: Children need to eat vegetables to be healthy.

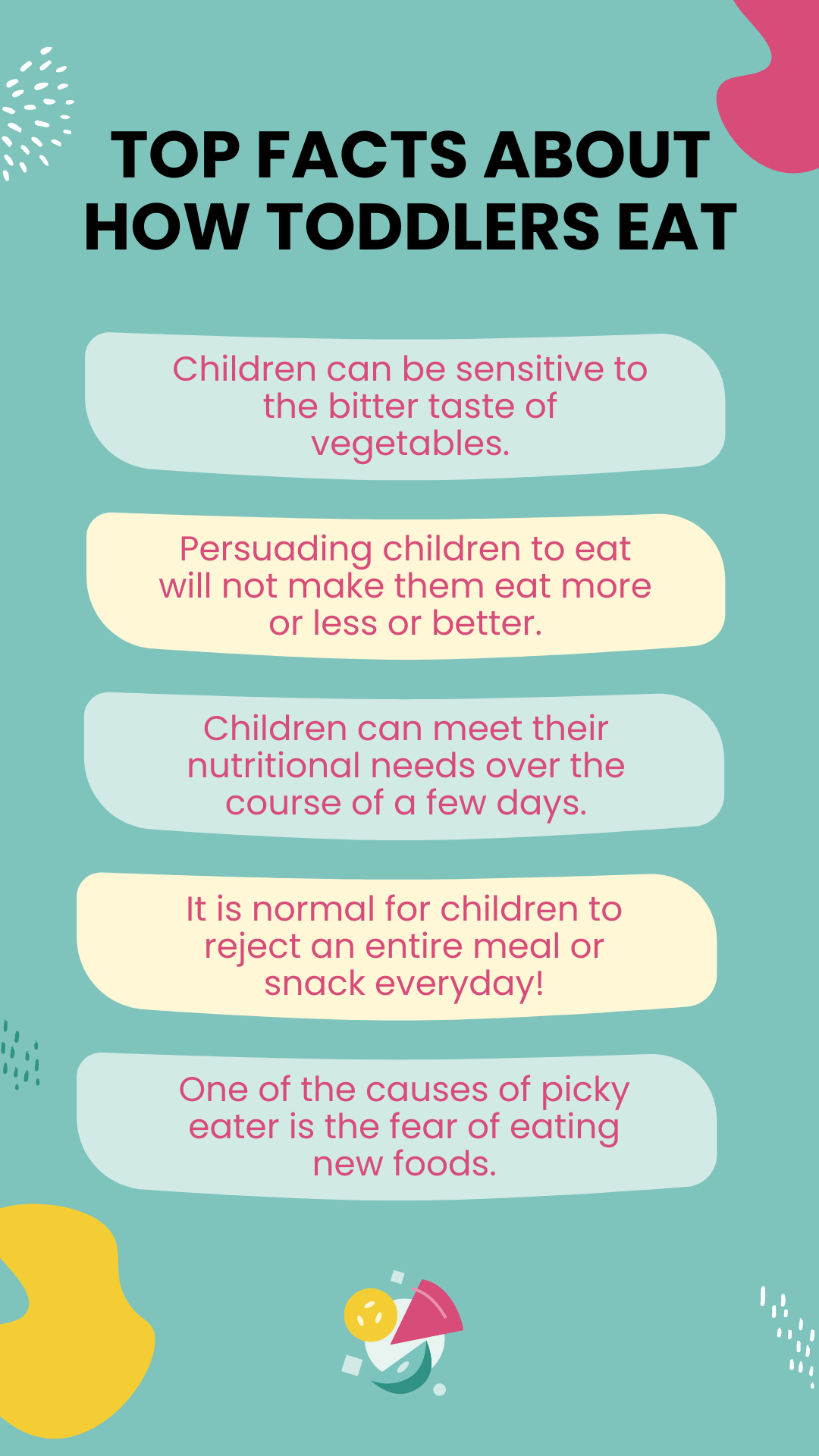

Not so! It’s good to try and help your child enjoy a varied diet, but children who eat fruit or have a multivitamin can do well even if they are not a veggie fan. In early childhood, children can be very sensitive to bitter tastes - it’s great to serve a wide range of foods but it’s important not to panic if the broccoli is being rejected.

❓MYTH 2: Toddlers sometimes need to be persuaded to eat.

In fact, persuading children to eat has the opposite of the desired effect… it makes their eating worse. Although it is pretty normal to use games, negotiation or bribery to encourage children to eat more (or to try foods) they do much better if you just relax and leave them to it. As we suggested above, you may be overestimating how much they need anyway.

❓MYTH 3: If adults don’t stop them, children may overeat.

Just as children don’t need to be persuaded to eat more, they also don’t need to be persuaded to eat less. If you restrict how much your child can have of a certain food, this will make them want that food more. They stop listening to their body and just want that food because you’ve accidentally made it seem extra desirable by limiting it. Sometimes it is necessary to limit food (because it is expensive or it has to be shared among the whole family) but letting children eat until they are full supports a positive relationship with food.

❓MYTH 4: Children need to eat balanced meals.

Dietitians think about nutrition in a ‘big picture’ way - what is important is what they have eaten over the course of 24 hours, or even over a few days. It is fine if they only eat pasta at dinner time, leaving the peas, and then enjoy an apple for their snack, leaving the crackers. Maybe they ate bacon for breakfast but didn’t want their nuggets later in the day. It’s all okay. Children are great at instinctively meeting their needs.

❓MYTH 5: Healthy children should be of average weight.

Worries about a child being too big or too small are extremely common - this can lead to parents persuading them to eat more than they want OR trying to make them eat less. As we’ve seen, both these things can actually make eating worse. Check with your healthcare provider if you are worried about your child’s weight. Often smaller or larger than average kids are simply that way because it is their genetic inheritance. Bodies come in all shapes and sizes!

👉🏼FACT 1: Young children’s food needs change a lot from day to day, week to week, and month to month.

One day they may be ravenous and another, not bothered at all. This is fine and simply reflects how much energy they are burning and what phase of growth they happen to be in.

👉🏼FACT 2: It is absolutely normal for young children to reject an entire meal or snack every day!

Imagine you are serving your two-year-old three main meals and two snacks…. They might turn their nose up at their lunch and decide to skip it altogether. This is much more likely to indicate that they didn’t need it, than that there is a problem.

👉🏼FACT 3: Caution about unfamiliar foods is to be expected in toddlerhood.

This is what scientists call food neophobia (fear of the new). Researchers think neophobia can be explained by a quirk of evolution: as children become more independent and mobile at around the age of one year, wariness about unfamiliar foods (think poisonous berries) could have been a life saver.

👉🏼FACT 4: Approximately one quarter of young children are ‘picky eaters’, and some estimates are even higher.

This is so common that we can say it is developmentally normal and to be expected. Toddlerhood is a time when children are experimenting with where the boundaries are, often they may practice asserting themselves at mealtimes. Add in a little natural neophobia and it is easy to see how picky eating can develop. This is usually just a stage, and most children** will have grown out of it by the time they are six years old.

👉🏼FACT 5: Children’s eating can change pretty suddenly as they reach the end of their first year.

and that little bub who was so excited to be introduced to solids can become a one-year-old who would rather be doing anything but eat. Research shows that it can be anxiety-provoking for parents to experience this shift when they weren’t anticipating it. However, if you know that food neophobia and picky eating are part for the course for many children, this change can feel less worrying.

* For some people, eating can be a really emotional and difficult area, especially where there is a history of disordered eating or dieting. If this is true for you, here are a couple of resources: ANAD , NEDA.

** For some children, accepting a limited diet is more than typical ‘picky eating’. For these children, assessment and support from their healthcare provider are recommended

Have any of these myths or facts surprised you? Do you think any of the advice above sounds hard to follow? EasyBites app can provide more tips and dive deeper into each topic or question you have!

Until next time,

Easy Bites

1. Leung, A. K., Marchand, V., Sauve, R. S., & Canadian Paediatric Society, Nutrition and Gastroenterology Committee (2012). The 'picky eater': The toddler or preschooler who does not eat. Paediatrics & child health, 17(8), 455–460. https://doi.org/10.1093/pch/17.8.455